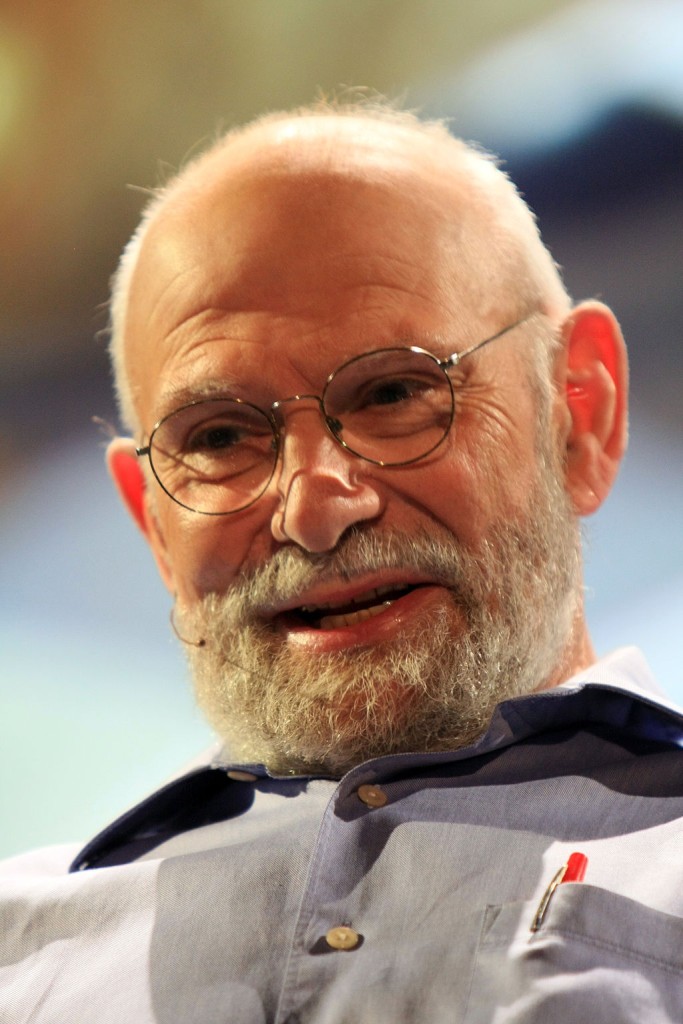

Anyone who rides a crowded subway every day can be forgiven for at least occasionally avoiding engagement with others, though Sacks provided an inspiring role model for human connection. Around me I saw young people, about whose well-being Sacks was most anxious because they never had the chance to develop “immunity to the seductions of digital life.” Many were playing video games, including crossword apps and, you bet, cruising Grindr. I read the “Life Continues” chapter while being crushed by humanity on a subway train during the morning rush. He probably never played a video game, but he may have been good at crossword puzzles: several details from his work, including the movie Awakenings, based on his 1973 book of the same title, have served as crossword clues. He enjoyed the luxury of a superlatively resourceful mind and he seems never to have experienced boredom, even during six-mile swims. Some were translated into dozens of languages. Which comes as a relief, considering the book’s final chapter, “Life Continues,” in which Sacks expresses concern for the future of humanity because of the isolation he perceives when people are engaged with their handheld electronic devices and not with one another.īefore his death nearly four years ago, Sacks published 15 books, most of them bestsellers that remain in print today. Hayes has assured us that the device in his lover’s hands is a magnifying glass, a tool that Sacks, blind in one eye and with cataracts, often employed when examining fine details of the natural world he loved. His hunched, hyper-alert posture could give a casual observer the impression that the world-renowned neurologist is texting a friend concerning some urgent matter.īut Mr.

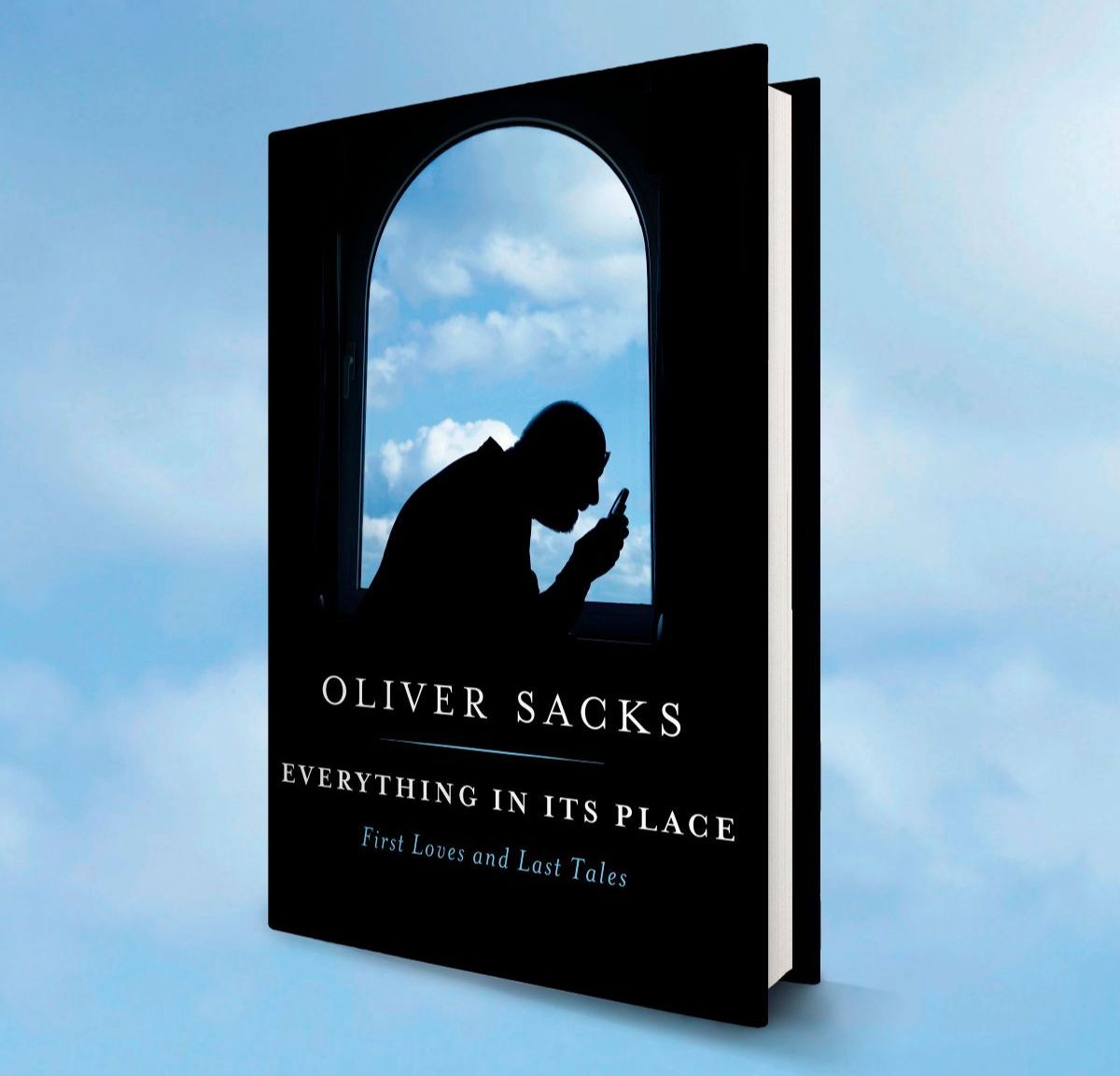

We see Sacks in profile, silhouetted against a softly clouded sky, with a handheld device close to his face. Oliver Sacks succeeded brilliantly at many endeavors, but when he tried his hand at pessimism, he failed miserably.Įverything in Its Place, the new posthumous collection of Sacks’s unpublished and uncollected essays, features on its dust jacket a photo taken by Bill Hayes, the man who taught a 76-year-old Oliver to kiss and provided six years of follow-up lessons.

‘Everything in Its Place: First Loves & Last Tales’ by Oliver Sacks

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)